Part of the series, "100 Years on Route 66 in 52 Weeks," published by the Missouri Press Association and distributed for reprint by its membership newspapers. Reprinted here with permission by MPA.

By Kip Welborn

It could be said that the whole world changed the day that the first automobile, created by J Frank and Charles Duryea, rolled down the streets of Springfield, Massachusetts. Within 15 years after Duryea’s “launch” of the first automobile made in the United States, 485 companies in the United States alone tried their hand at building automobiles, and in 1906 came Henry Ford, whose mass production model made automobiles accessible to a wide segment of the population.

In 1909 car owners, by and large, lived in cities and towns. They wanted to leave the towns and go places. However, the maze of paths and trails that served as the means to “go places,” though marginally passable for wagon or beast, were not passable for the automobile if there was a drop of rain or a flake of snow. The automobile required flat surfaces made of materials that would stay flat and solid despite the conditions. And the person who laid the groundwork for making those flat surfaces possible was a bicycle and automobile salesman, and the creator of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Carl Fisher.

What Fisher did, in 1912, was to conceive and help develop the Lincoln Highway, the first transnational highway to cross the entire United States. At this point any funding, state or federal, for highways was limited at best. As such, the Lincoln Highway was by and large privately funded. The Lincoln Highway Association was formed to raise funds and recruit workers to maintain and construct the Lincoln Highway. Meanwhile, Fisher spoke to whoever would listen about the highway. His sales pitch focused on the automobile having limited use outside urban areas and on the dreams that a machine built for going places created. As Fisher echoed to the crowd at the Old Deutsches Haus in Indianapolis: “Let’s build it before we’re too old to enjoy it!”

And the road Fisher created, extending from New York City to San Francisco, spawned a vast number of what became known as “auto trails.” Road associations were formed to adopt existing paths and fund the construction and maintenance of the auto trails. The route that a substantial amount of Route 66 would follow across Missouri was an auto trail that was known as the Ozark Trail, which extended in its entirety across Missouri and on to Las Vegas, New Mexico.

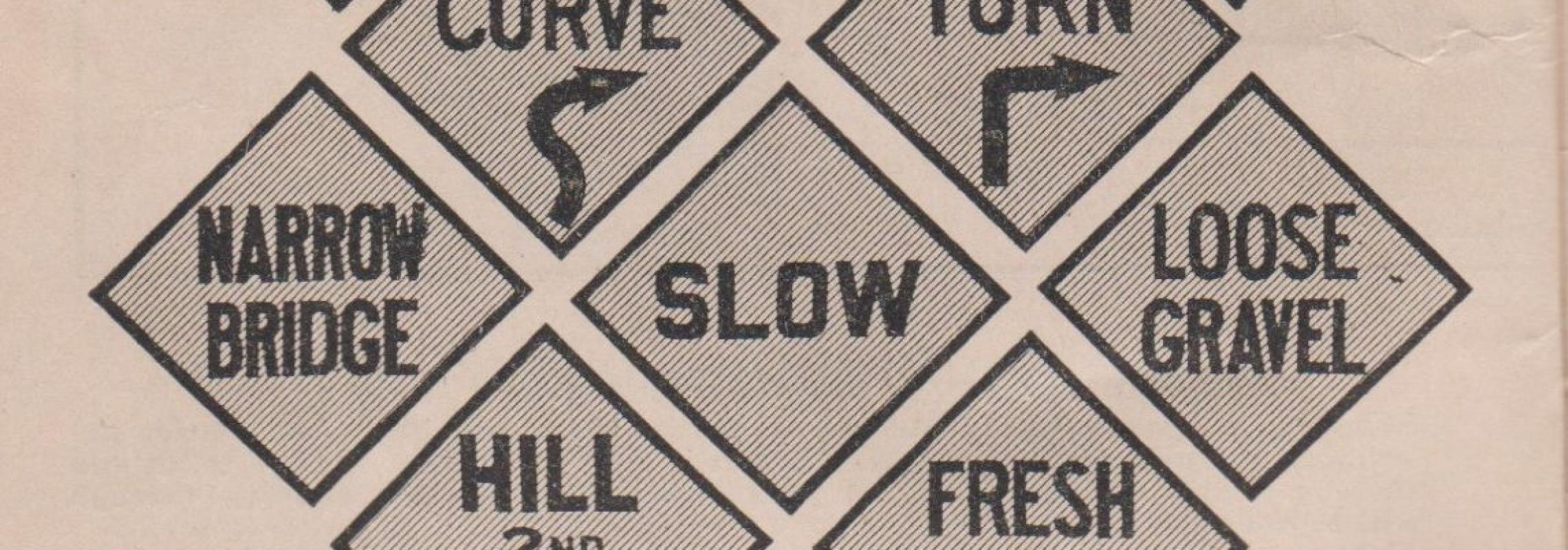

And with the birth of the auto trail came the first “system” of road signs. Following the lead of the Lincoln Highway Association, which created road signs with red and white bars and an “L” in the middle, the multitude of auto trails were marked with either letters or colors or a combination of both. The Ozark Trails Association marked its trail with a sign that had “OT” letters in the middle of the sign, with green stripes at the top and bottom. The OTA also went to great lengths to mark its highways with obelisks at certain intersections to show the direction and distances to various cities.

However, even with the signage in many places it was very difficult to figure out how to get where you wanted to go. Signage in rural areas, particularly the farther west you went, was sporadic and difficult to find. “Signs” were often painted on poles with arrows pointing in a given direction, to where no one knew (on Missouri highway maps, they were actually called “pole signs”). Sometimes you would have several haphazardly painted signs on the same pole, many of which looked a lot alike. As such, while there was signage, the “signs” often created more problems than solutions.

To their credit, however, auto trails were a significant upgrade from the wagon trails that existed previously, and the shortcomings in the auto trails system compelled state and local governments to fund the construction of roads and create signage that gave travelers a far better idea of where they were going. The state of Missouri made its initial contribution with the passage of the Centennial Road Act in 1921. The Act enabled the Missouri State Highway Commission to develop a 7,500-mile system of primary and secondary roads. And as part of that system, signage was created to designate primary (state) highways and secondary (farm to market) roads. In 1921, the State Highway Commission designated No. 14 for the route that was the Ozark Trails and would become Route 66. With that designation came Missouri’s first state highway signs. Some of these signs were painted on bridges, some were standalone. All were clearer to follow than what the traveler experienced with the auto trail.

State Route 14 would serve Missouri travelers for five years. However, Congress passed the Federal Highway Act of 1921, which, according to Bill Swift in his book about the evolution of the U.S. highway system, Big Roads, “was the foundation for modern highway building in the United States, and remains the single most important piece of legislation in the creation of a National Network.” The creation of that national network, of which Route 66 would be a major part, was left to Thomas McDonald, then the head of the Bureau of Public Roads. And McDonald’s righthand man in this endeavor was Edwin James.

In 1925, a joint board of transportation officials was convened to create a “uniform system for designating the routes” in the new federal highway system. Acting on the inspiration from Edwin James, a system was created where the primary east-west routes would be even numbers and the primary north-south routes would be odd numbers. Once this was established, again with inspiration from James, uniform signage was developed which would provide effective guideposts for travelers. The early state highway maps for Missouri presented a pictorial description of these signs. The state highway signs took on the shape of the state of Missouri while the federal highway signs took on the shape of the shield that they have today.

One of the routes designated as part of the new interstate (federal) highway system was for the road that took travelers from Chicago to Los Angeles, the road that, in Missouri, was designated as State Route 14. Originally that road was designated as U.S. 60, but McDonald bowed to pressure from Kentucky and Virgina and gave that number to a route from Virginia Beach, Virginia, to Brenda Junction, Arizona. At a meeting at Colonial Motel in Springfield, on April 30, 1926, B.J. Peipmeeier, Henry Sheets and Cyrus Avery, the highway commissioners of Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma, respectively, took inspiration from John Page, the chief engineer for the Oklahoma Highway Commission, to utilize the number 66. While it did not end in a zero, it was a number that would be remembered and would not confuse travelers and was certainly catchier than “Route 62.” As such, the trio agreed that “Route 66” was the proper designation for the route from Chicago to Los Angeles.

And so, on April 30, 1926, a Western Union Telegraph was sent from Springfield to Thomas McDonald, chief of the Bureau of Public Roads, that the number 66 would be accepted for the new U.S. highway route that extended from Chicago to Los Angeles. And that shield would guide travelers down the Mother Road, from the day U.S. highway shields went up in 1926 to this day, as a historical route that reminds us all of the importance or Route 66 to the modern history of this country, and to anyone who has revved up their engines, put their foot on the gas, and hit the road!

Kip Welborn is a member of the board of directors of the Route 66 Association of Missouri. He has written articles for several Route 66 publications, including the National Historic Route 66 Federation Magazine, American Road Magazine, and the official magazine for the Route 66 Association, Show Me Rote 66 Magazine. He is currently a staff writer for the Show Me Route 66 Magazine. Email him at rudkip@sbcglobal.net.